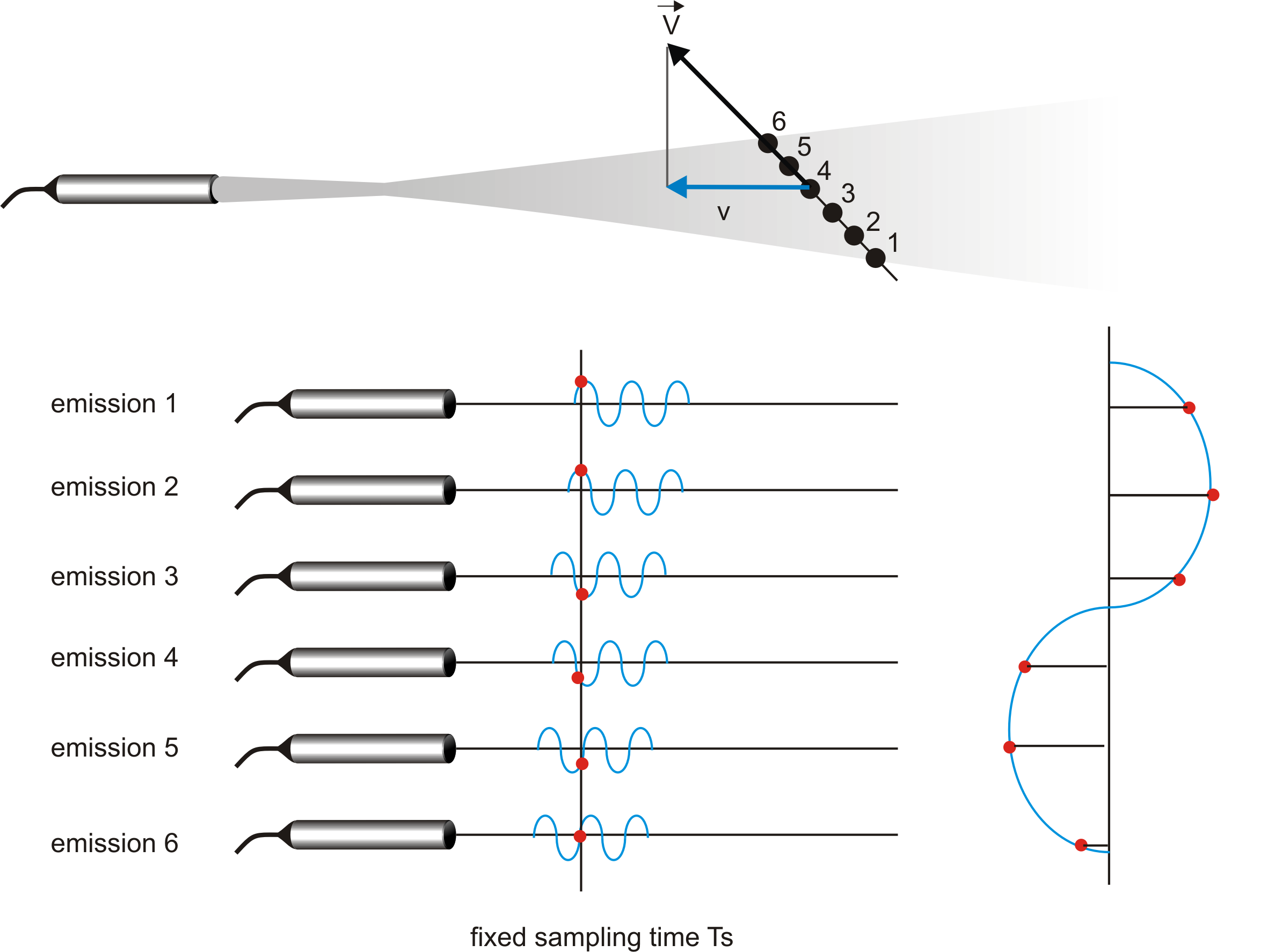

The Doppler ultrasound technique was originally applied in the medical field and dates back more than 30 years. The use of pulsed emissions has extended this technique to other fields and has opened the way to new measurement methods in fluid dynamics.

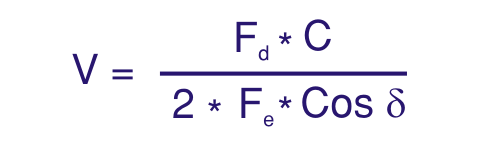

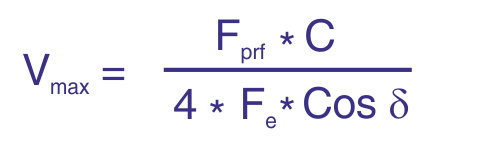

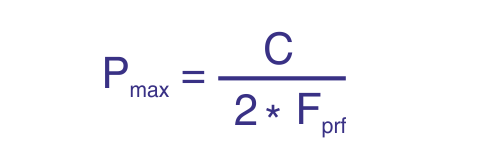

The term "Doppler ultrasound velocimetry" implies that velocity is measured by detecting the Doppler frequency in the received signal, similar to Laser Doppler velocimetry. In pulsed ultrasonic velocimetry, however, velocities are calculated from particle displacements between successive pulses, and the Doppler effect plays only a minor role. Many publications, even recent ones, fail to make this distinction, resulting in incorrect system descriptions and misinterpretation of various physical effects.